We’ve all been enchanted by the stories: 900 Google employees became millionaires during IPO, 1000 Facebook employees became millionaires, 55 people working at Whatsapp were acquired for $19 Billion, and so on. But the truth is most startups don’t end up this way. They either close, get acqui-hired, get acquired, and IPO (in descending exponential order of probabilities).

Closing down isn’t fun to explore, so we’ll ignore them. The good news about the other three outcomes is you have a chance of making a non zero amount of money. The bad news is most think this is not a chance and they will end up making money anyway. Why can’t founders and employees make money if the startup is acquired?

The Venture Guys

The venture guys are slick. As much as you sell them a dream (that your company will be worth $10B in 8 years), they sell you a dream (that you can become a millionaire thanks to their help). And yes, the $10B exits do happen and they get a lot of press but again, the vast majority of startups don’t reach this stage. And VCs are vultures when it comes down to getting their money out (even it comes at their cost). Remember what Travis Kalanick said (and famously didn’t adhere to): VCs are not your friends

Liquidation Preferences

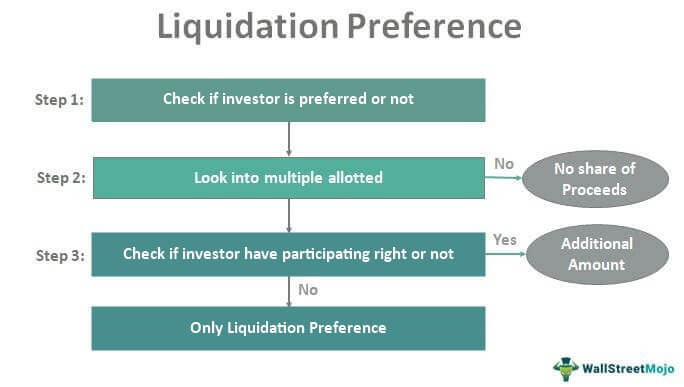

A liquidation preference is simple: in the event of liquidation (merger, acquisition, or IPO), there are certain rules that need to be followed (by contract) before everyone gets their money. These rules are usually defined by a company’s investors, which is agreed upon by the company before receiving funding.

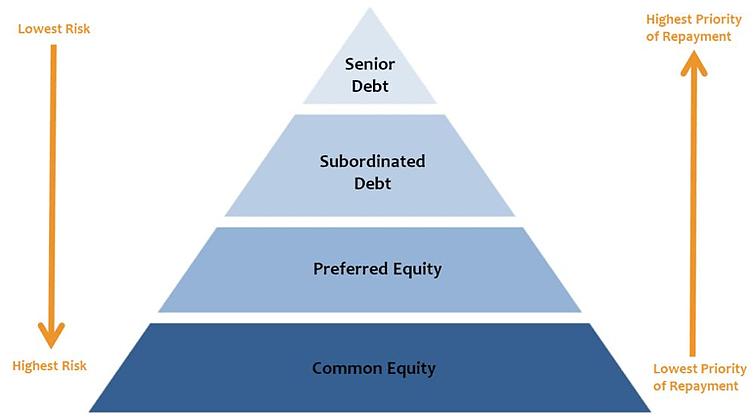

You may have come across some of these rules in the context of a public company. A public company has different layers of debt in its capital structure. Senior debt, different levels of junior debt, warrants, options, etc. are defined in the capital structure of a company so creditors (i.e. people who give money to the company) can get part or whole of their money back in the event things go south.

In a private company, at the early stages, there is only VC money, and in later stages, debt money comes into the picture. Dealing with debt, and how the different structures of debt work is a topic for future threads. With respect to VC money, VCs like liquidation preferences (in extreme cases, they may impose warrants but private co warrants have been subject to so much criticism that VCs don’t do it anymore).

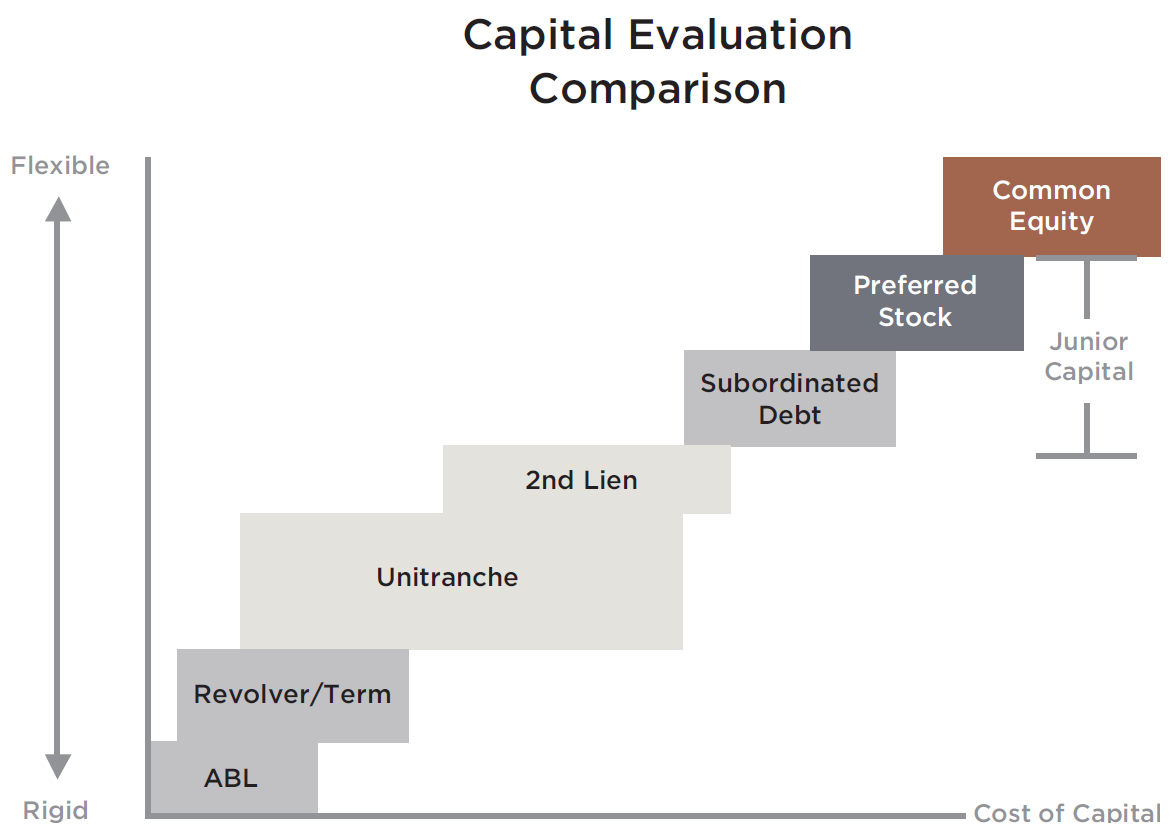

There is another component to capital structure, which is the cost of capital for the company to borrow. Certain structures offer a lower cost of capital at the expense of flexibility during a liquidation event.

But lets leave capital structure for a separate article and focus on liquidation preferences. Liquidation preferences have three components: a multiple, participating / non participating, and a cap / no cap. Seniority among investors is a parallel thread in addition to these three components.

A multiple is simple: there is a multiple attached to the amount of $$ a VC puts into a company: 1x preference, 2x preference, 5x preference, etc. Lets assume a VC invests $10M into a company. At 1x preference, the VC is entitled to get their $10M back first before employees and founders are paid. At 2x, they are entitled to get $20M back, and so on. The existence of preference implies the division of shares in the company into two categories: preferred stock, and common stock. Preferred stock is held by investors (sometimes founders too), and common stock is held by employees. Common stock does not come with any privileges. Preferred stock comes with a list of privileges (voting, board seats, liquidation preferences, etc.).

Participating / non Participating means you either get a part of the equity payout after liquidation preferences, or you get an option to get part of the equity payout after liquidation.

Lets take the same $10M VC example, assume the VC owns 15% of the company, holds a 1x preference, and that the company is sold for $100M. Participating and preferred means an investor gets their preferred money at 1x (ie $10M) AND gets 15% of the REMAINING $90M ($13.5M). So total payout to the VC is $23.5M and the employees and founders get $76.5M.

Non participating and preferred means an investor has the OPTION to convert their 15% stake to common shares and get a $15M payout or to hold their preferred shares and get a $10M payout. As you may guess, it is not economically rational for an investor to hold on to preferred in this case, so they will EXERCISE this OPTION and get $15M, leaving $85M to the employees. So total payout to the VC is $15M and the employees and founders get $85M.

Remember, every option that you give to another entity (person / professional) carries a value, regardless of whether you think it has value or even whether you realize that it is an option. In the above case, the price of the option is zero for participating and non zero in non participating. I will explore this in depth in a later article.

Cap places a ceiling on how much investors can be paid with liquidation preferences. In the above example, if the VC invests $10M for 15% with a 1x participating liquidation preference and 3x cap, it means the VC is entitled to $30M of the proceeds from a sale from preferred stock. The VC still has the OPTION to convert preferred to common and realize a higher payout. Caps usually exist at later stages of funding (Series C+).

Why should employees care?

If you are an employee, you want to be hopefully be paid a lot of money from the work you’ve done at your startup. 4 years ago, you signed up as one of the first 10 team members, got 1% of equity and $150k in exchange for your hard work, and your company is being acquired for $100M.

You would have received something called the “stock option value calculator” before you signed the offer. It would have contained two metrics: value at exit, and dilution. You would have seen that at $100M, your stake would be “diluted” 50%, and you own 0.5% of the remaining, so you’re paid $500k from the sale. Right? Wrong.

Employees should care about capital structure of their company because it affects their outcomes, and because is not within their control (no employee except the founder and later, board, agree to capital structures). This is a classic example of an embedded option that employees do not price in, but write to founders and management for free (in most cases). What is the value of this option?

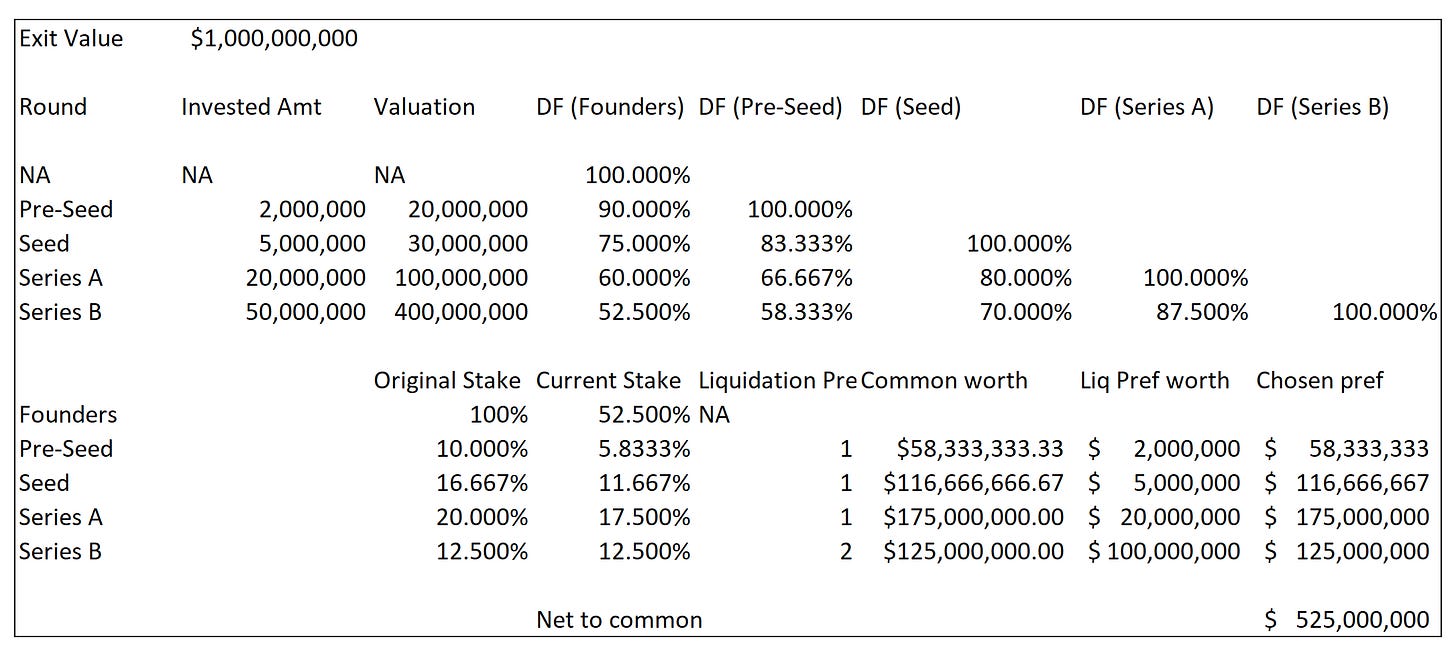

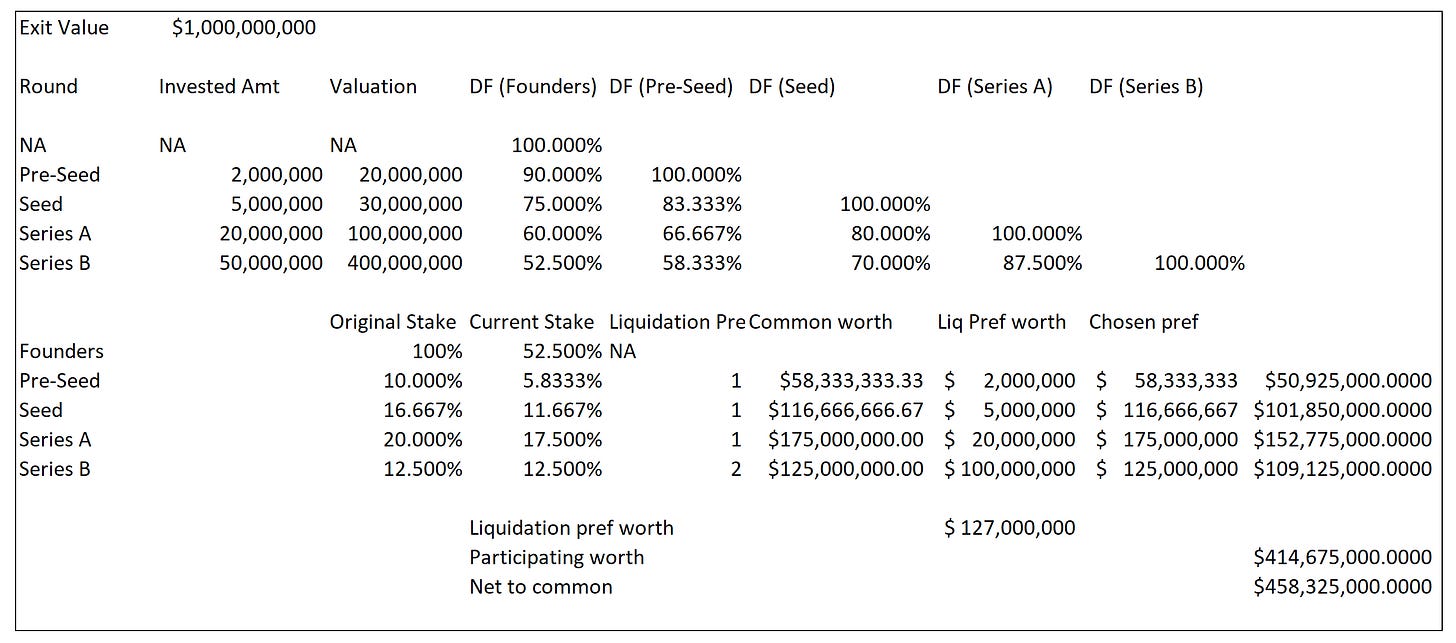

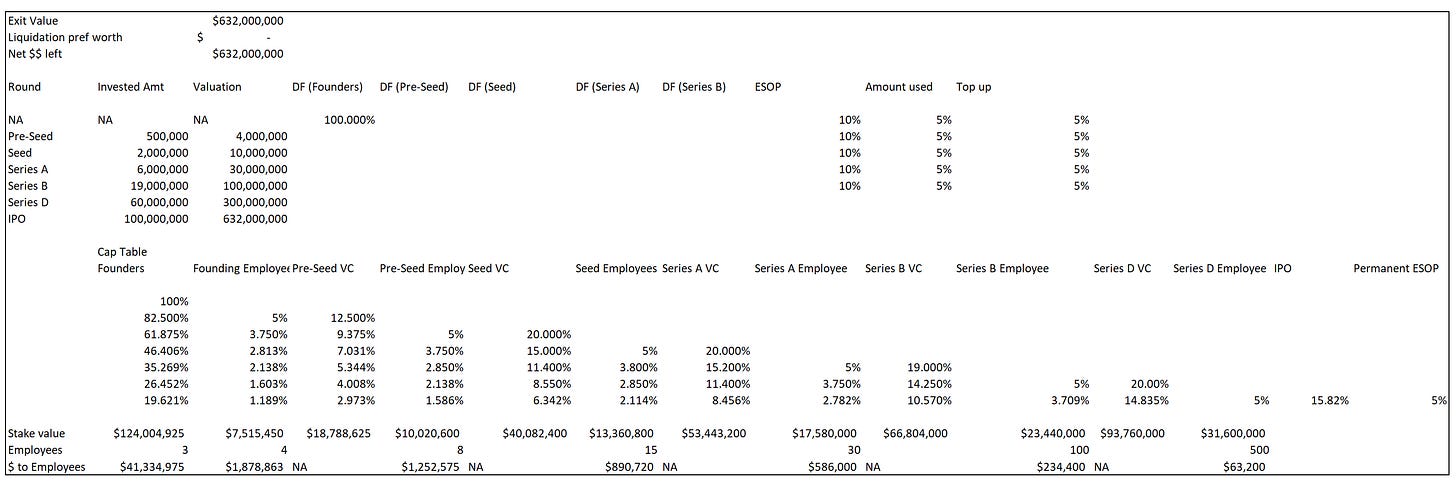

Assume the following funding rounds, and assume each round is by distinct VC firms, and assume all rounds have 1x liquidation preference, with Series B being participating preferred. Also assume the startup is liquidated (through whatever means) at $1B

Pre-Seed ($2M at $20M)

Seed ($5M at 30M)

Series A ($20M at $100M)

Series B ($50M at $400M)

Exit Liquidation ($1B)

Assume the co has two co-founders, each of whom owned 50% before pre-seed. And assume you are one of the first 10 employees, who signed an offer before pre-seed, for $150K and 1%. How much do you get at exit?

Round 1: 2M at 20M post, round dilution 10%, your stake is worth (1-10%)*1% = 0.9%

Round 2: 5M at 30M post, round dilution 16.7%, your stake is worth (1-16.7%)*0.9% = 0.75%

Round 3: 20M at 100M post, round dilution 20%, your stake is worth (1-20%)*0.75% = 0.6%

Round 4: 50M at 400M post, round dilution 12.5%, your stake is worth (1-12.5%)*0.6* = 0.525%

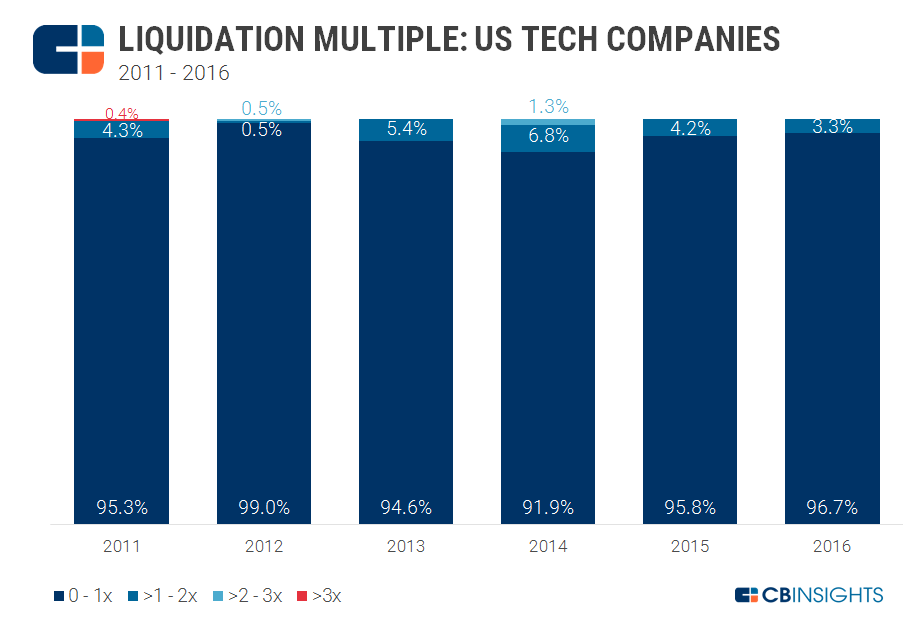

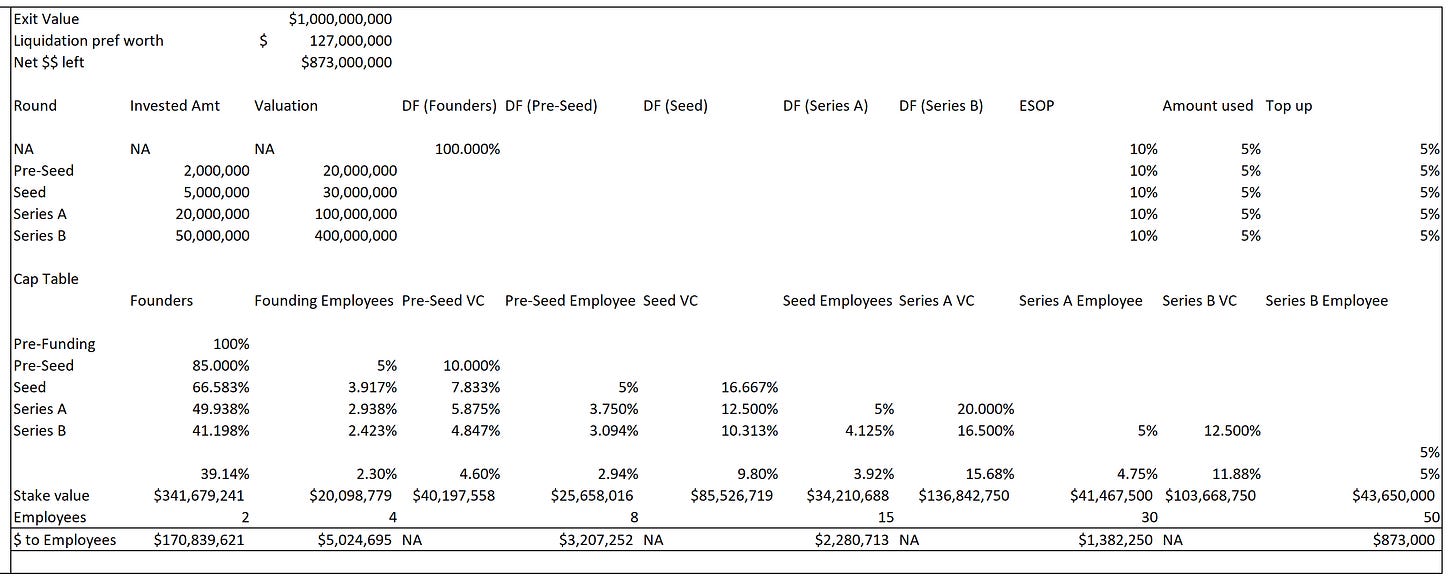

By now, you should know you aren’t getting 0.525% or $5.25M. Here’s a table showing how much you’d get (still a higher bar since there are few rounds and the terms are relatively nicer) in three scenarios: participating, non participating, and a more realistic ESOP-topping and participating scenario.

So, if you joined as employee #5, had 1.25% of the company when joining, your final equity stake at liquidation will be 0.575% (46% of initial equity), and your payout will be $5.024M or 0.502% of liquidation deal size (since there are participating preferred holders). In other words, 60% dilution in the event of a unicorn exit at Series B. You still make decent money, just not the money you thought you’d make.

Unicorn now vs Decacorn 10 years later

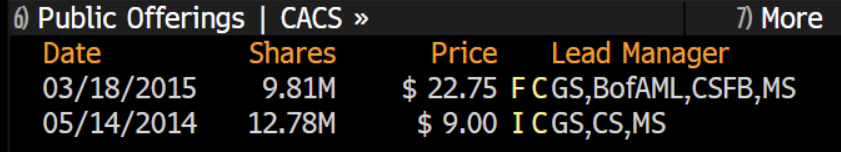

In recent news, Zendesk was acquired for $10.2B (down from $17B six months earlier, don’t be too greedy). Zendesk is interesting because it IPO’d in 2014 for $632M. 8 years later, acquired for 10.2B. In raw terms, Zendesk returned 36% annualized compared to the S&P’s 11% and Nasdaq’s 16.6%. Seems like a great investment for the team? Or is it?

Round wise deal size info is not available for Zendesk (apart from $ raised), so we’ll put in some conservative numbers to model how much equity is left with the founders.

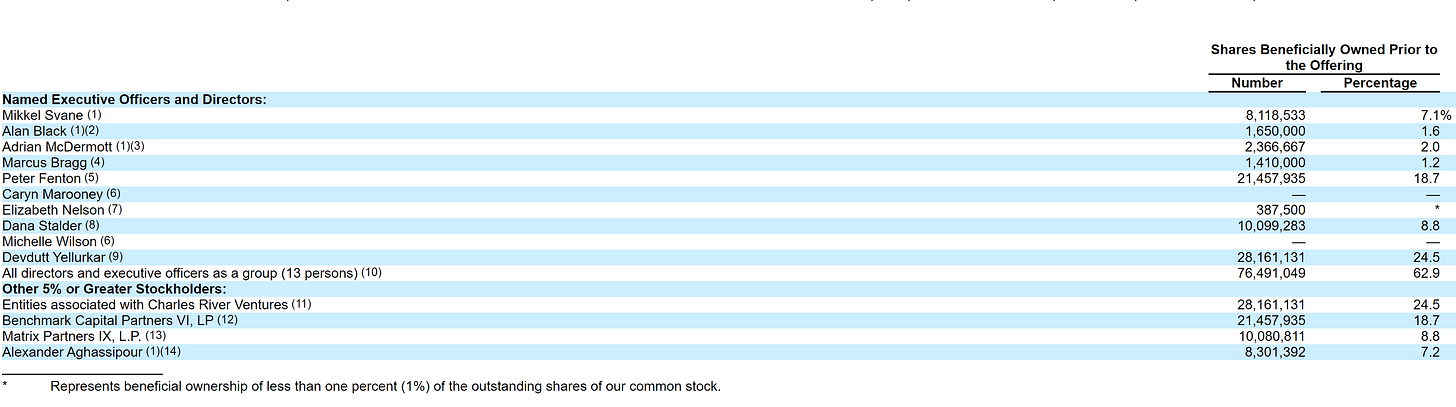

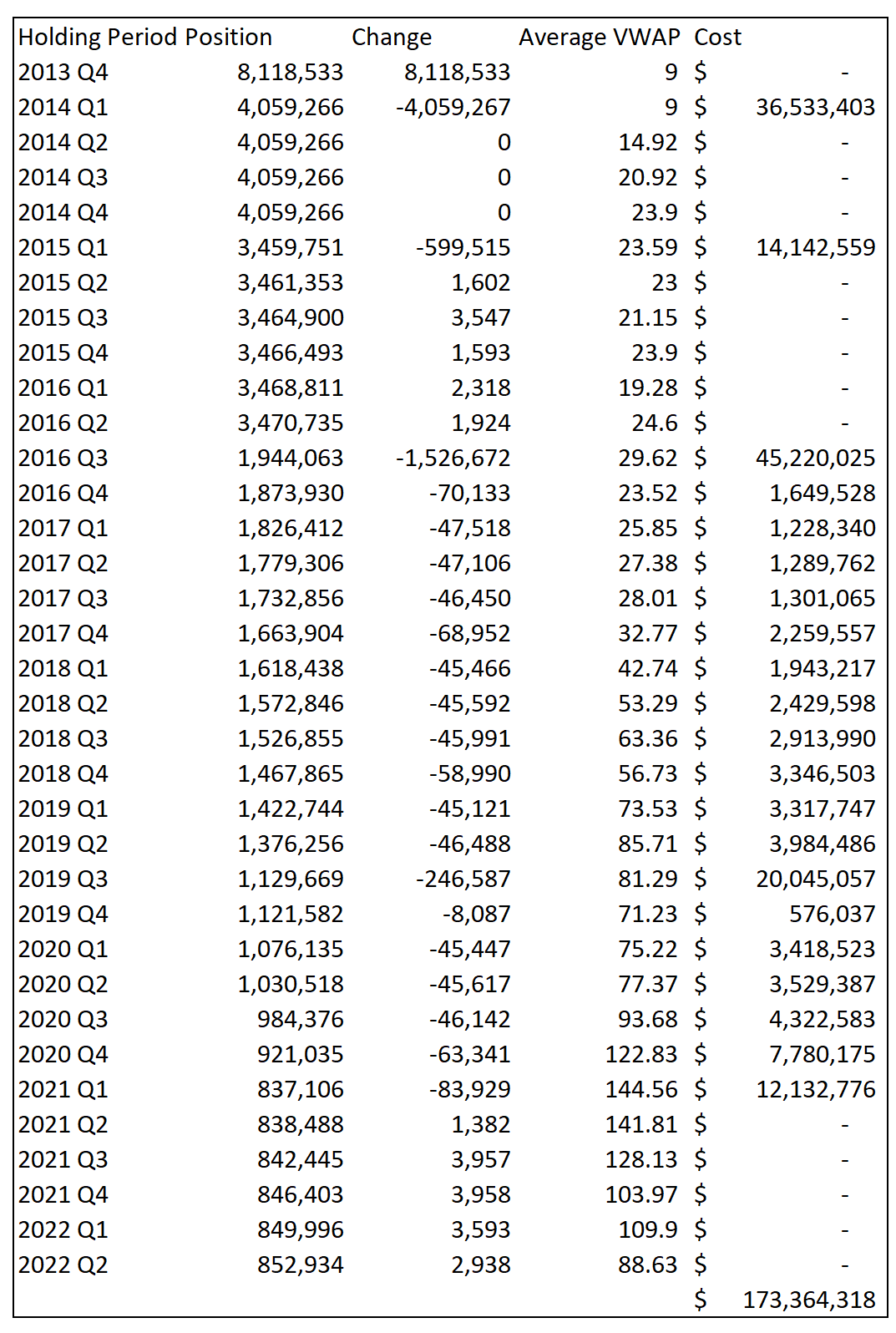

The 19.6% we model is pretty close to the actual number, which seems to be 7.2% for the two co-founders. Lets take 7.1% at IPO, which nets $73M (Zendesk IPO’d at $9 per share)

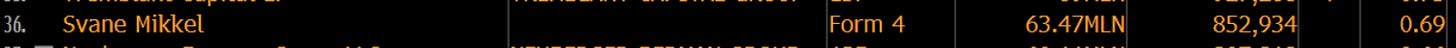

Founder and CEO Svane currently owns 0.69% of common, which roughly equals $69M.

Taking a deeper look, looks like he sold his shares at the IPO, then at the secondary offering, and then slowly over time. On a cost basis, this equals ~$173M. Adding current $69M, that equals $242M.

$73 to $242M in 9 years is a 14.2% annualized rate of return for Svane. As mentioned above, the S&P 500 returned 11% and the Nasdaq 100 returned 16.6%. In other words, Svane lost money compared to the broad tech index. Not a great investment now, is it? I am pretty sure Svane and Zendesk could have gotten a better deal had they shopped around before, but most founders are pigeonholed into believing illusions they created, so they don’t look at their cos from the outside.

If you were an employee, I hope you exercised your shares at decent prices.

Conclusion

If you’re an employee, do the exit math. If you’re a founder, do the potential exit math. Take the early exit if it makes more sense, invest (even in indexes!), start new cos, and help others. The headache of running public cos is not worth it if you can’t beat the index handily.

Find the Excel model used in above screenshots here.

Good post